There is a lively debate around the long-run performance of Italy since the Middle Ages. This column introduces new estimates of Italy’s GDP per capita from 1300 to 1861. The estimates are constructed using the demand-side approach and are based on nearly 95,000 price/wage observations from almost 200 locations. The estimates provide new insights on the drivers of the ‘Little Divergence’ between Italy and the countries of the North Sea region (England and the Netherlands) after the Middle Ages. Additionally, it explores the long-term origins of the economic divide between North and Southern Italy.

The long-run performance of the Italian economy in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period has always been controversial, with a prevailing pessimistic view of an absolute and relative decline since the 17th century and a lively debate about its causes (Cipolla 1952, Rapp 1976, Sella 1979, Alfani 2013). The pioneering estimates of the GDP per capita of the Centre-North by Paolo Malanima (2011) have offered a more optimistic view, with a long-term stagnation until the 18th century, but so far they have not been matched by a comparable series for the South.

In our paper (Federico et al. 2024), we estimate, for the first time, yearly series of GDP per capita for Italy and its two constituent macro-areas (Centre-North and South) from 1328, the earliest feasible date, to 1861, the year of the unification of the country. The data on production are very scarce and inconsistent and thus, as standard in the literature, we use data on prices and wages, following the so-called demand-side approach. This method yields a series of GDP per capita expressed as a real output index using a two-step procedure: first, we estimate agricultural output per capita using a simple demand function featuring real wages as a proxy for income (adjusting daily wages with a new estimate of change in working days), a price index of agricultural goods and a price index of manufactures. In the second step, we compute the share of non-agricultural production in GDP based on estimates of the share of non-agricultural employment (inferred from urbanisation rates), adjusted by the relative productivity of non-agricultural workers versus agricultural workers. Finally, we compute a purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rate of regional currencies with pound sterling in 1850 and we use it to convert our index series of GDP per capita into 1990 Geary-Khamis dollars, to make it comparable with the long-term data available for other European countries. Our estimates are constructed using a new large-scale dataset comprising nearly 95,000 wage/prices observations from 169 locations for wages and 186 for prices, retrieved from both archival and published sources. This large-scale dataset has an unprecedented coverage and represents a marked improvement with respect to previous studies.

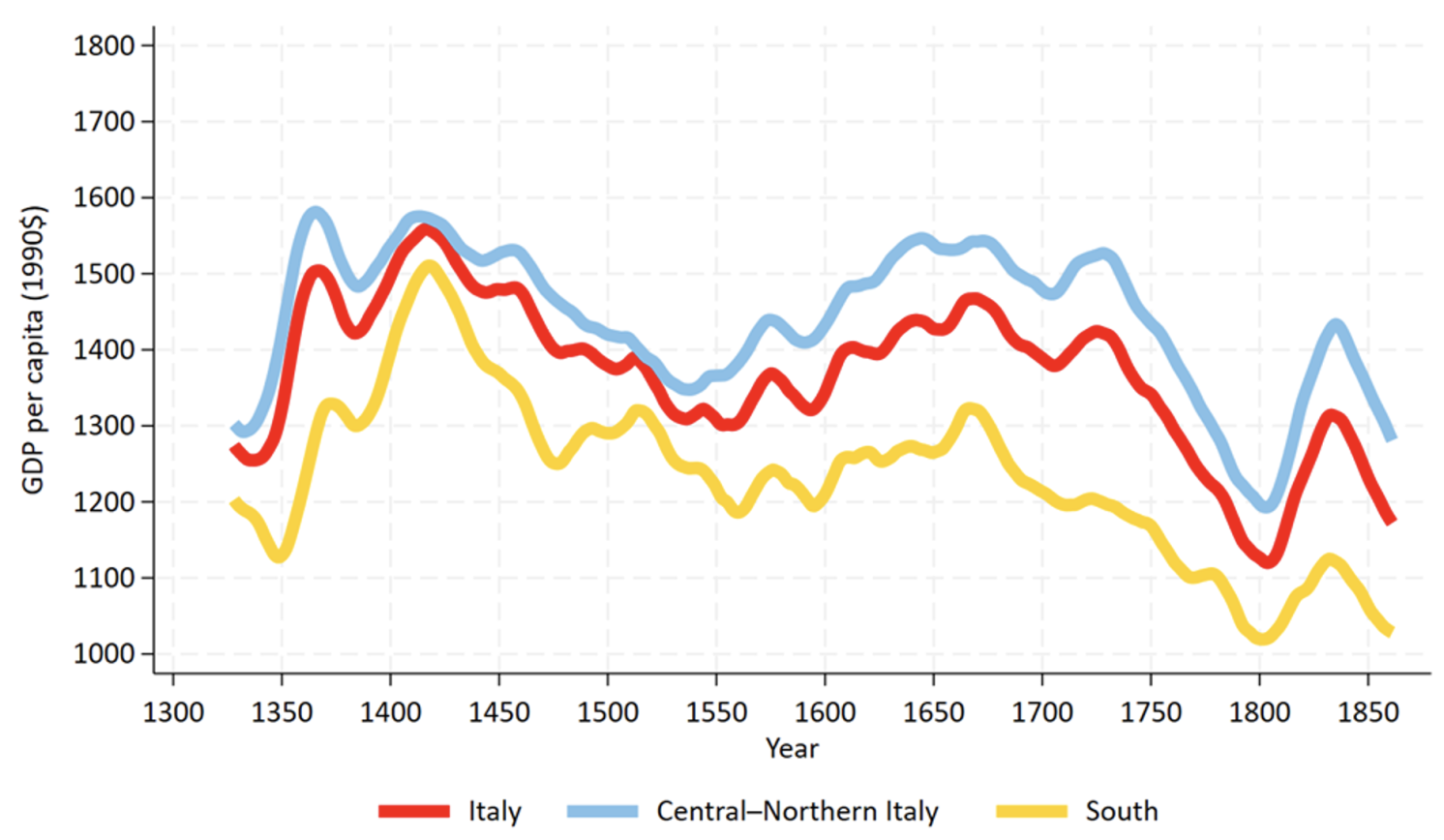

Figure 1 plots our estimates of GDP per capita in 1990$ for Italy and its constituting macro-areas (smoothing yearly fluctuations with an Epanechnikov kernel). The national series fluctuates widely around an average of $1360. The GDP hit an all-time peak in the early decades of the 15th century, during the early Renaissance, declined until the mid-16th century, recovered in the 17th century, and remained quite high until the 1720s. We find a sharp decline for the rest of the 18th century and trendless fluctuations in the first decades of the 19th century.

The series for Central-Northern and Southern Italy show a similar pattern, albeit the recovery phase of the 17th century seems weaker in the South. Notably, southern GDP at its 1800 trough was extremely low, being one third lower than the level of the Middle Ages.

Figure 1 GDP per capita: Italy, Centre-North and South, 1328-1861

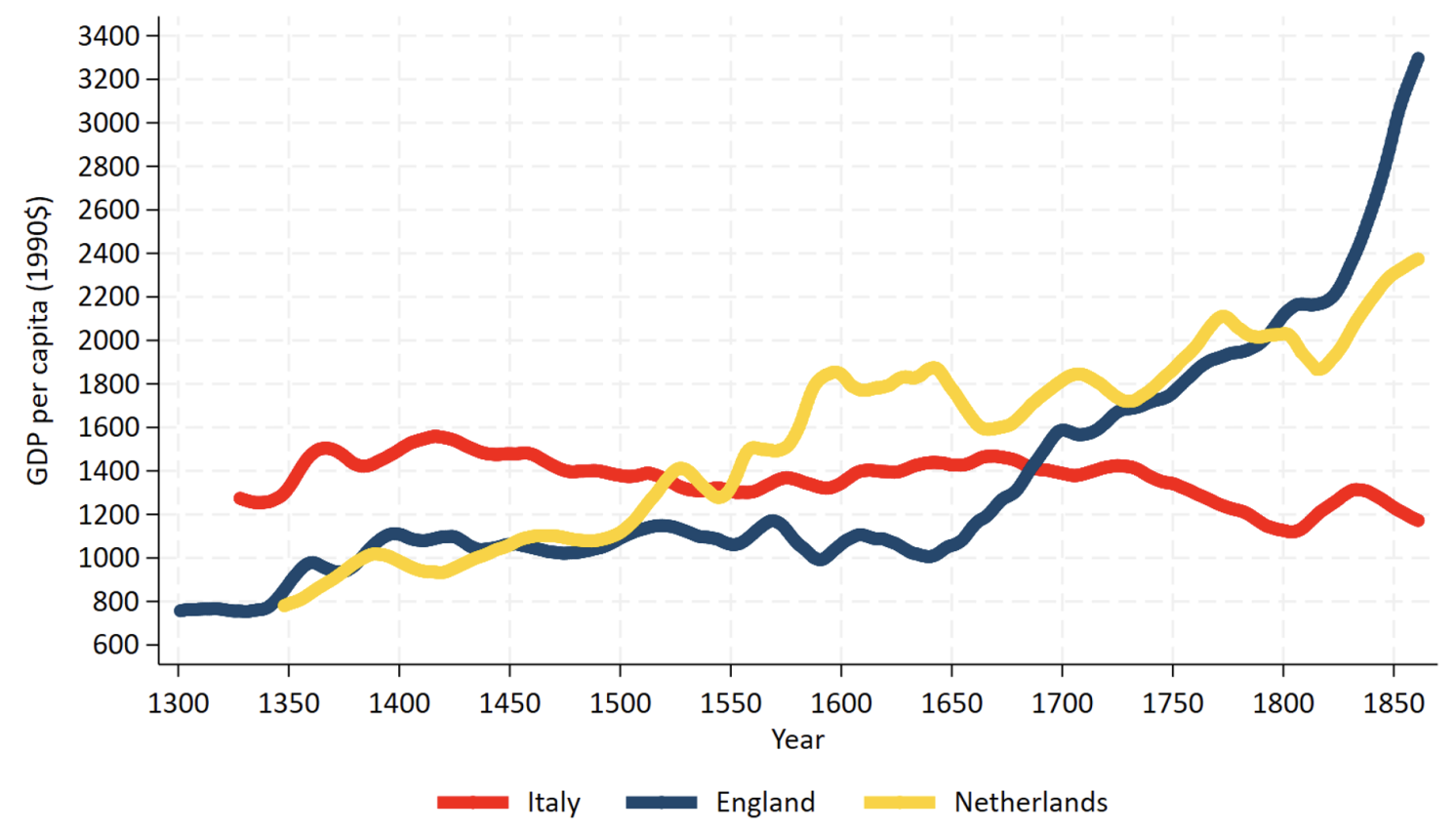

Figure 2 compares Italy, with the two ‘winners’ of the so-called ‘Little Divergence’: the Netherlands and England. Up to 1500, Italian GDP per capita remained substantially higher than that of the other two countries. The Netherlands overtook Italy around the mid-16th century, a little earlier than the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of the Dutch economy (de Vries and van der Woude 1997). Our estimates indicate that the decline of Italy relative to England begins in the second half of the 17th century, with England forging ahead after 1680. England further advanced during the 18th century, driven by the Industrial Revolution. By 1861, Italian GDP per capita was only slightly more than one third of the English level.

Figure 2 GDP per capita international comparisons: Italy vs. England and the Netherlands, 1328-1861

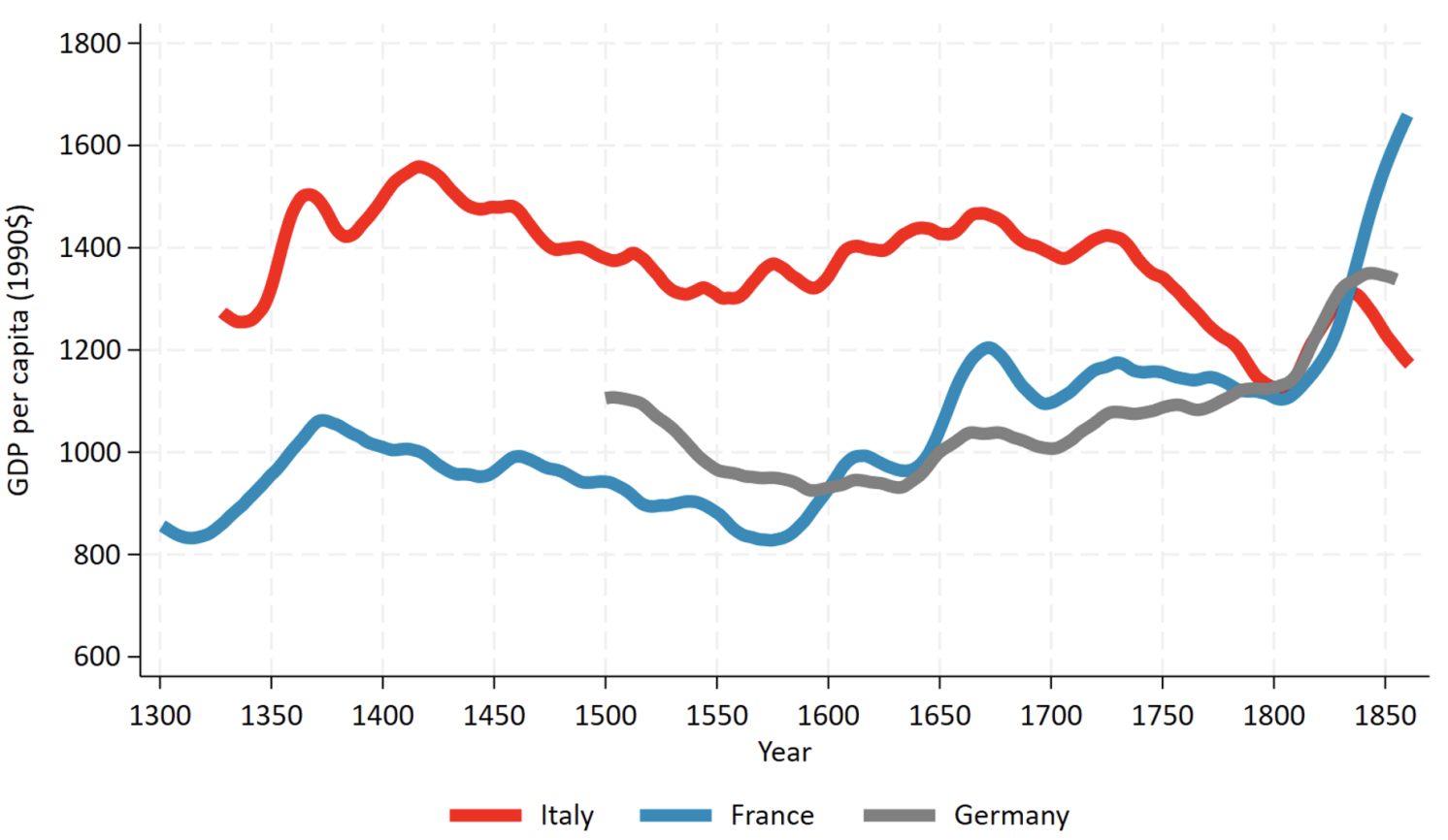

Notwithstanding its decline relative to the Netherlands and England, Italy enjoyed a substantially higher level of GDP per capita than France and Germany until the start of its absolute decline in the early 18th century (Figure 3). By 1800, Italy had lost all its advantage, and in the central decades of the century both France and, to a smaller extent, Germany forged ahead.

Figure 3 GDP per capita international comparisons: Italy vs. France and Germany, 1328-1861

Our research sheds new light on the origins and the persistence of the regional divide between Northern and Southern Italy, an issue which has long puzzled economists, historians, and social scientists and has not yet been settled. In particular, the historical origin of the gap remains highly controversial. In a seminal contribution, Putnam (1993) argued that the roots of this enduring economic divide can be traced back to the distinct civic traditions that emerged during the Middle Ages, leading to significantly higher levels of social capital in the Centre-North regions compared to the South. At the other end of the spectrum, authors such as Capecelatro and Carlo (1972) claimed that the regional divergence was largely a consequence of the political unification in 1861, and the misconceived development policies implemented by the newly founded state. Outside of academia, this latter interpretation, championed by a group of popular historians who dub themselves as ‘Neo-Bourbonist’, has recently gained traction with best-selling books and receiving extensive coverage in newspapers and magazines, and sustained visibility on social media.

Over the last 20 years, our understanding of the regional differences in economic performance from the political unification in 1861 to WWI, the so-called ‘Liberal Age’, has significantly advanced thanks to systematic quantitative reappraisals of GDP per capita (Felice 2019, Chiaiese 2024), industrial production (Ciccarelli and Fenoaltea 2013), inventive activities (Nuvolari and Vasta 2017), real wages (Federico et al. 2019), and living standards (Felice and Vasta 2015, Vecchi 2017). Conversely, the period before the unification remains largely uncharted.

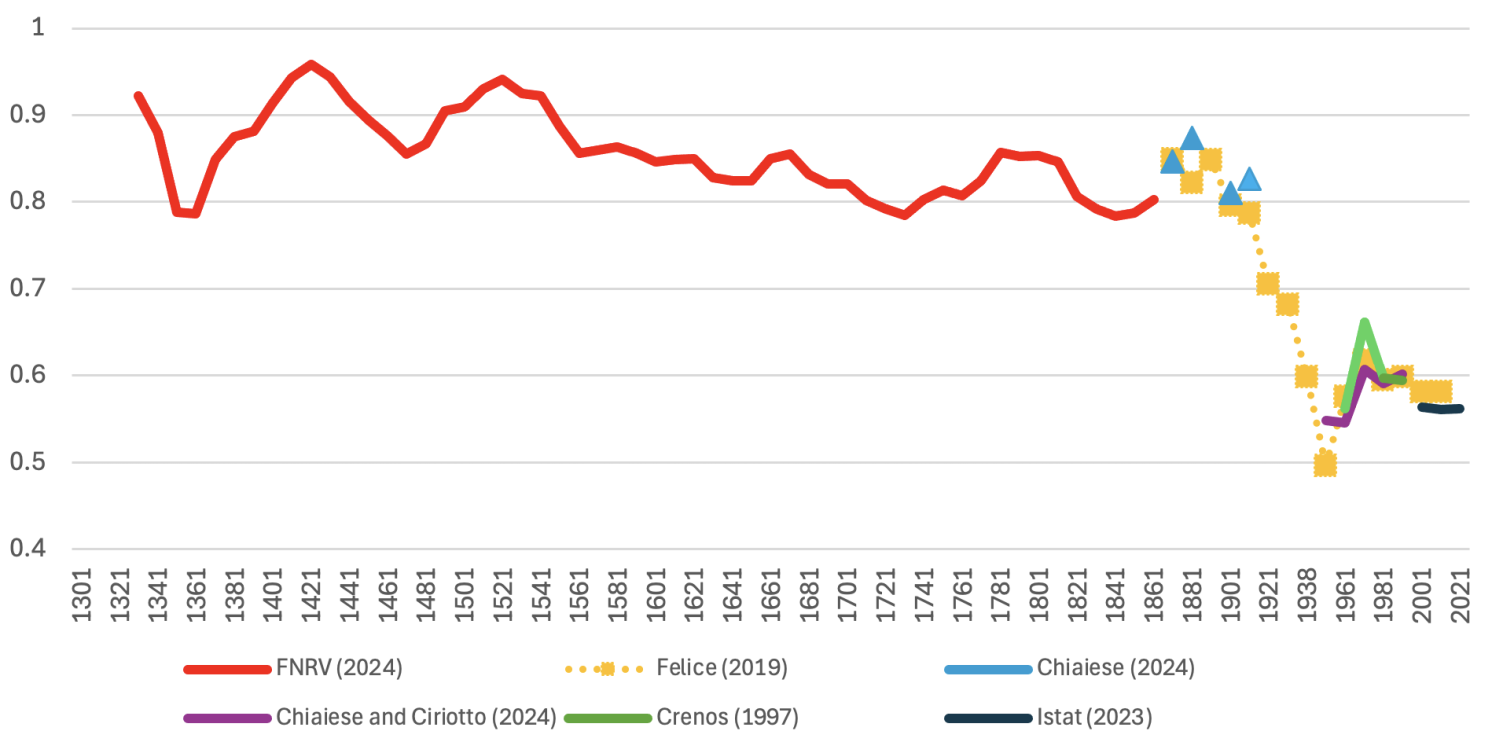

Figure 4 plots a ‘quasi-millennial’ series of the regional divide in GDP per capita constructed by splicing our new series with the recent estimates for the post-1861 period.

Figure 4 The South/Centre-North gap in GDP per capita: A quasi-millennial perspective, 1328-2021

As one would have expected, the gap during the period 1328-1861 mostly remained restricted between 10% and 20%. Indeed, in the pre-industrial economies, inherent limits constrained economic growth effectively setting a ceiling, even for the most dynamic regions. These constraints prevented significant economic divergences between rich and poor countries or regions from emerging. The gap between Centre-North and South in the pre-industrial period was high just after the Black Death, then shrank in the next century, with a minimum in the mid-14th century. From the early 17th century onwards, the South experienced a prolonged secular phase of ‘slow-motion’ divergence until around 1850, when the gap was as wide as 400 years earlier. The level of the gap that we estimate in 1850 is broadly consistent with the most recent estimates (Felice 2019, Chiaiese 2024) for 1871. Clearly, this latter finding dispels the neo-Bourbon nostalgic view that, just before unification, the Southern regions enjoyed levels of economic prosperity and living standards comparable to those of the Centre-North. The North zoomed ahead since the start of industrialisation in the 1890s and the gap further widened during the Fascist era. Following WWII, there was a brief spell of convergence (1950–1970) during which the Southern regions began to catch up. However, this phase was short-lived, and since the 1980s, the gap has been once again expanding.

To conclude, Italy’s peak in GDP per capita in the early phases of Renaissance was not reached again before the unification. To put it bluntly, Masaccio’s Italy was richer and more prosperous than Cavour’s. The South was consistently poorer than the Centre/North and the divide was dramatically widened by industrialisation since the early 20th century. These long-term historical roots can explain why development policies for the South were plagued more by failure than success.

References

Alfani, G (2013), “Plague in seventeenth-century Europe and the decline of Italy: an epidemiological hypothesis”, European Review of Economic History 17(4): 408-430.

Broadberry, S N, B M Campbell, A Klein, M Overton and B V Leeuwen (2015), British economic growth: 1270-1870, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Capecelatro, E and A Carlo (1972), Contro la ‘questione meridionale’, Roma: Savelli.

Chiaiese, D (2024), “Provincial estimates of the Italian Value Added in the liberal age, 1871-1911”, Rivista di Storia Economica / Italian Review of Economic History 40(1): 3-43.

Chiaiese, D and V Ciriotto (2024), “Italy in Wide-Angle: Workforce, emigration, population and GDP at the provincial level in Republican Italy (1951-1991)”, mimeo.

Ciccarelli, C and S Fenoaltea (2013), “Through the Magnifying Glass: Provincia Aspects of Industrial Growth in Post-Unification Italy”, Economic History Review 66(1): 57–85.

Cipolla, C M (1952), “The decline of Italy: the case of a fully matured economy”, Economic History Review 5(2): 178-187.

Crenos – Centre for North South Economic Research (1997), Regio-It 1960-96, University of Cagliari.

de Vries, J and A van der Woude (1997), The First Modern Economy. Success, Failure and Perseverance of the Dutch Economy, 1500-1815, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Federico, G, A Nuvolari, L Ridolfi and M Vasta (2024), “Italy’s Long-Term Economic Performance: GDP Estimates from 1300 to 1861”, CEPR Discussion paper 19406.

Federico, G, A Nuvolari and M Vasta (2019), “The origins of the Italian regional divide: Evidence from real wages, 1861–1913”, Journal of Economic History 79(1): 63-98.

Felice, E and M Vasta (2015), “Passive modernization? The new human development index and its components in Italy’s regions (1871-2007)”, European Review of Economic History 19(1): 44-66.

Felice, E (2019), “The roots of a dual equilibrium: GDP, productivity, and structural change in the Italian regions in the long run (1871–2011)”, European Review of Economic History 23(4): 499-528.

Malanima, P (2011), “The long decline of a leading economy: GDP in central and northern Italy, 1300–1913”, European Review of Economic History 15(2): 169-219.

Nuvolari, A and M Vasta (2017), “The Geography of Innovation in Italy, 1861–1913: Evidence from Patent Data”, European Review of Economic History 21(3): 326–56.

Pfister, U (2022), “Economic growth in Germany, 1500–1850”, Journal of Economic History 82(4): 1071-1107.

Putman, R D (1993), Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rapp, R T (1976), Industry and economic decline in seventeenth-century Venice, Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Ridolfi, L and A Nuvolari (2021), “L’histoire immobile? A reappraisal of French economic growth using the demand-side approach, 1280–1850”, European Review of Economic History 25(3): 405-428.

Sella, D (1979), Crises and continuity. The Economy of Spanish Lombardy in the Seventeenth Century, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

van Zanden, J L and B Van Leeuwen (2012), “Persistent but not consistent: The growth of national income in Holland 1347–1807”, Explorations in Economic History 49(2): 119-130.

Vecchi, G (2017), Measuring Wellbeing: A History of Italian Living Standards, Oxford: Oxford University Press.