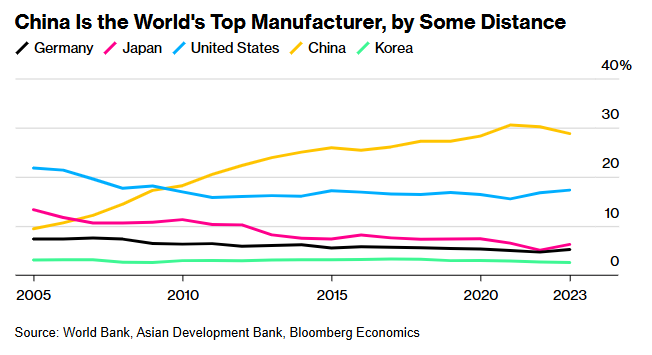

With the weeks running down on 2024, Chinese policymakers are already in a position to declare “mission accomplished” on their (almost) decade-long Made in China 2025 project.

Despite headwinds including major tariff hikes by successive US administrations, the worst domestic housing slump in modern times and an increasing fragmentation of the global economy into competing blocs, China’s manufacturing sector has gone from strength to strength. Bloomberg Economics calculates it has the biggest goods-trade surplus relative to world GDP since post-World War II America (when most everybody else’s industries had been wrecked.)

And, as this newsletter has noted, China is ahead in many newer areas. Bloomberg Economics assesses the nation as a global leader in five of 13 key technologies, including electric vehicles, high-speed rail and solar panels. Also notable: “China’s export surge has increasingly come from domestic, not foreign firms in China,” says Senior Geo-Economics Analyst Gerard DiPippo. (See the full note on the Bloomberg terminal here.)

The rub for President Xi Jinping and his team, however, is that this magnificent success doesn’t necessarily help lift Chinese median incomes. Beijing views “high tech” as a synonym for productivity, but that doesn’t work when most of the labor force isn’t in high tech, or manufacturing for that matter. Indeed, the dreaded Japan parallel still looms for China: Japanese car companies emerged as global leaders in the 1980s and 1990s just as the country’s economy descended into its lost decades.

This week in the New Economy

- Apple ships $6 billion worth of iPhones from India in just six months.

- Rise of electronic payments fails to stop Swiss plans for new banknotes.

- A lack of green buildings leaves Hong Kong behind Singapore and Tokyo.

- AstraZeneca’s China push left it exposed—part of broader European trend.

- The “central bank for central banks” is leaving the digital-payment project.

For China, the road ahead may only get tougher in the coming years—even within the manufacturing sector. It’s increasingly clear that Donald Trump’s embrace of tariff hikes in 2018 as part of his trade war was just the start of a major trend in global economics. In a sense, once the Republican pushed the US across that line, it became a newly realistic option for everyone.

It’s taken some time, but many countries and trade blocs now have legislative or regulatory pathways for imposing tariffs. The European Union this week officially imposed higher levies on Chinese electric vehicles. Colombia last week joined Latin American peers including Brazil, Mexico and Chile in slapping tariff hikes on Chinese steel to shield local producers.

And of course, if Trump manages to defeat Vice President Kamala Harris on Tuesday, in all likelihood Chinese manufacturers will face a new wave of tariff hikes from Washington.

Last time, the levies didn’t prove devastating in part due to the Covid pandemic, which sent demand for Chinese goods soaring across the developed world as governments sought to protect citizens and economies with income support. And just as that effect faded, Russia became a big growth market for China, thanks to Western sanctions over its full-scale invasion of Ukraine and Xi’s eager embrace of the Kremlin amid the unprovoked destruction.

The rolling 12-month total of Chinese exports to Russia and central Asian neighbors has soared to $178 billion from about $100 billion before Vladimir Putin’s 2022 attack, according to Thomas Gatley at Gavekal Dragonomics.

But in a Trump 2.0 version of tariff hikes, there isn’t another Russia waiting in the wings—a $2 trillion economy that can “become economically dependent on China when declared a pariah by the Western world,” Gatley wrote in a note Thursday.

And even under the tariff and export-control measures currently in place, some Chinese industries are hurting. The nation’s share of the global semiconductor market has dropped, Bloomberg Economic analysis shows. China’s pharmaceutical sector also faces stepped up scrutiny, as US lawmakers consider the Biosecure Act to restrict Chinese biopharma firms. If the legislation passes as many observers anticipate, it could become another precedent for other developed countries to follow.

Against a backdrop of subdued domestic demand, protectionist trade measures will only add to China’s deflationary tendencies, pressuring companies to hold down prices to keep market share. Gatley concludes that this price dynamic amounted to “the biggest cost imposed on the Chinese economy by Trump’s first round of tariffs.”

US Trade Policy May Be Heading Into a New Paradigm

Trump has floated a universal tariff along with high levies on Chinese imports

Which takes us back to China’s domestic economy. Unless the Communist leadership is able to turn depressed private-sector confidence around and stoke job and income growth well beyond the manufacturing sector, the nation will continue to risk weak growth that leaves its per-capita GDP far below the rich world.

Xi’s team is expected to announce its latest economic-support effort in coming days. Many observers have focused on the importance of a large fiscal package. It’s worth keeping in mind that Japan pushed through plenty of those back in the 1990s. Beijing’s attitudes toward the private sector, and especially services, may instead by the key element to watch for.